The nights may be drawing in, but night-time is the best time to view Given To Chance at Nomas Projects this November.

The collaborative project between NEoN Digital Arts and the AHRC-funded research project The Future of Indeterminacy: Datification, Memory, Bio-Politics at the University of Dundee, Given To Chance displays five video works in the window gallery on Ward Road in Dundee city centre.

Although many of the works are still viewable in daylight hours, it’s once the sun has set that the work really shines. The set-up allows the work to be viewable 24-7 and though it may be cold the pieces by Jennifer Gradecki and Derek Curry, Martin Disley, Dina Kelberman, Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo, and Enorê are captivating enough to distract from your own numb fingers and toes.

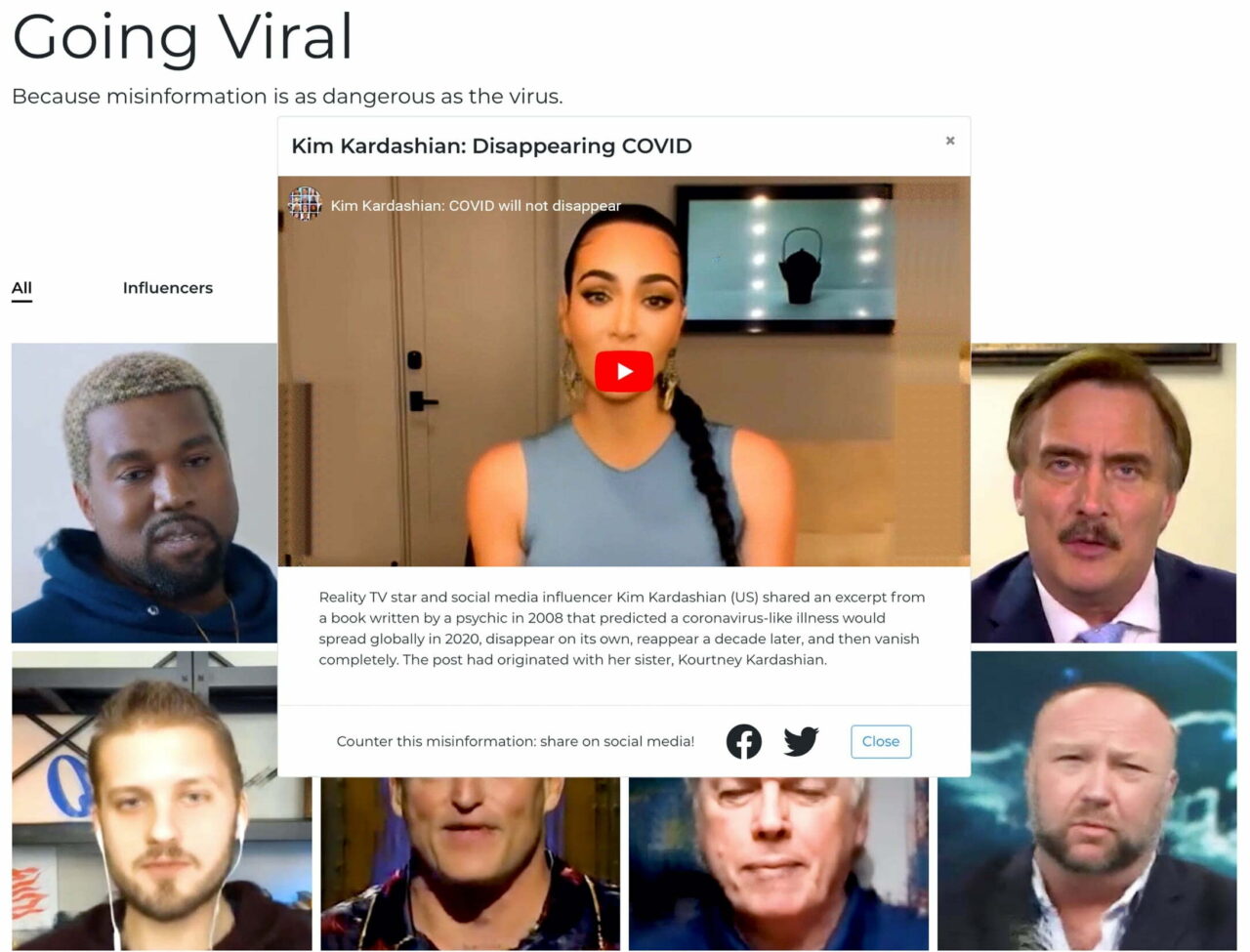

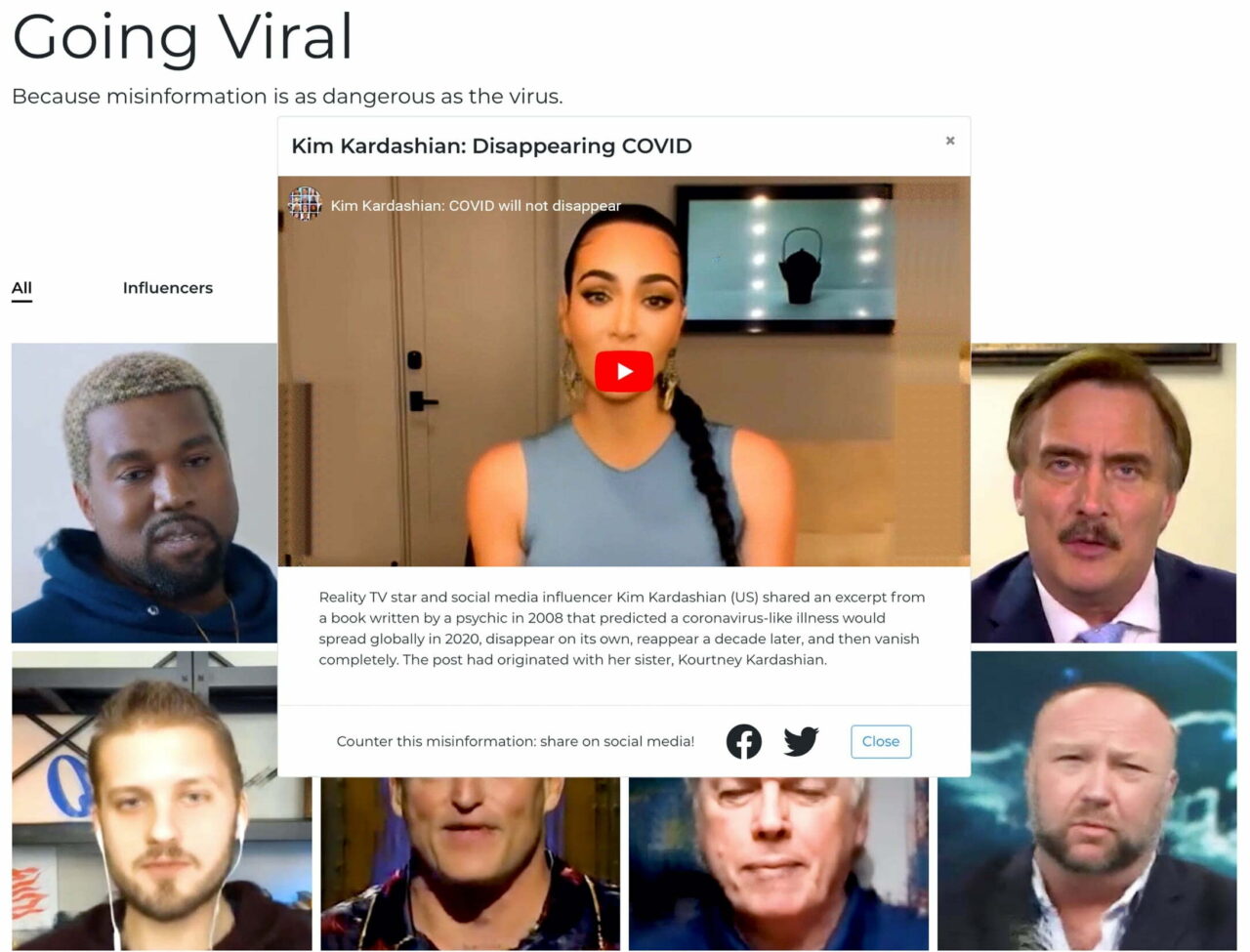

Taken from left to right, the first screen shows Gradecki and Curry’s short video work Going Viral. The looped film explores the dangerous lies spread by celebrities, influencers and people of power during the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. One by one the figures appear against a black background, their faces flickering like low res GIFs as plain white text lays bare the harm they’ve been causing. Actors like Woody Harrelson and Gwyneth Paltrow appear, as do musicians like Kanye West, Madonna, and M.I.A. as well as Kim Kardanshian. There’s Brazilian President Jair Bolsanaro, former Member of the Italian Parliament Alessandro Meluzzi and, of course, Donald Trump.

For Trump the text reads: “US President Donald J. Trump has erroneously stated that bleach and UV light may help to internally treat coronavirus. He has repeatedly claimed that hydroxychloroquine is an effective and safe treatment for COVID-19, despite the lack of evidence that it is effective, and some evidence that it can cause heart problems.” A square image of Trump sits alongside this statement. Blue suit, blue tie, hair coiffed, he shuffles nervously.

After each ‘influencer’ segment the screen goes black except for a single statement in white that reads; “Help counter this misinformation: goingviral.art”. Where the viewer to follow the link they would find themselves invited to contribute to the interactive artwork. Text on the website reads, “[Going Viral] invites people to share COVID-19 informational videos featuring algorithmically generated celebrities, social media influencers, and politicians that have previously spread misinformation about coronavirus. In the videos, the influencers deliver public service announcements or present news stories that counter the misinformation they have spread. Viewers are invited to share the videos on social media to help intervene in the current infodemic that has developed alongside the coronavirus.”

When asked to unpack the term “infodemic”, Gradecki and Curry explained, “By infodemic we mean when misinformation and disinformation spreads widely, often going viral online, like a virus during an epidemic. Misinformation (unintentionally false information) and disinformation (intentionally false information) are nothing new, but they have developed especially rapidly alongside the pandemic. The term infodemic can be traced back to the SARS outbreak in 2003, but it came to our attention in February of 2020 when the WHO Director, General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus stated: ‘We're not just fighting an epidemic; we're fighting an infodemic. Fake news spreads faster and more easily than this virus, and is just as dangerous’.”

The artistic duo are both assistant professors in Art + Design at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts. Before developing Going Viral for NEoN they had made a similar, shorter film called Infodemic. The video work uses the voices of medical experts and journalists - talking sensibly about the dangerous of misinformation (and disinformation) during a time of global crisis - and manipulates video footage of the celebrities, politicians and social media influences who’ve been spreading these lies so that instead they are telling the truth. When Gradecki and Curry saw our Indeterminacy/Share call out they saw an opportunity to develop this project further.

“When we applied to the call, we were developing a neural network generated video called Infodemic, which raises questions about the constructed nature of online information,” say Gradecki and Curry. “Unlike Going Viral, the neural networks in Infodemic are trained on multiple people simultaneously, so the video morphs between different talking heads or is a glitchy Frankensteinian hybrid of multiple people. But, like Going Viral, the messages in Infodemic are taken from academics, medical experts, and journalists.”

The project raises some interesting questions, such as; whether social media platforms should block fake news and misinformation as a matter of policy, if it should be illegal to spread misleading information that might cause someone physical harm (like recommending people drink or inject bleach), how we should approach personal anecdotes that appear to promote or support harmful ideas, and the danger of pushing people into further radicalism and conspiracy by ridiculing or dismissing their genuine concerns.

“We certainly wouldn't want a multinational corporation to be in a position to determine what is true or false,” say Gradecki and Curry. “The problem with social media is twofold, presenting misinformation along actual news has a legitimating effect for the misinformation, and the business model of social media platforms provides a financial incentive for social media outlets to spread misinformation via recommendation algorithms because it stimulates interaction from users.”

“When anecdotes and opinions are posted online, there is the possibility that they will be shared and become part of a larger, public conversation. It is one thing for an individual to share an anecdotal story about something that happened to them or someone they know, it's another thing for that anecdote, or a handful of anecdotes, to be given the same credibility as a scientific study or journalistic investigation.”

“We think the solution is to educate people in media literacy. People could be taught how to be critical of sources they find online, especially on social media, and what sources of information are held accountable by different institutions. For example, scientific and academic articles undergo a peer review process, and while the process is not perfect, there is some level of accountability and fact checking. Likewise, professional journalists are held to standards of the profession, which requires some level of fact checking.”

“When people feel they aren't being listened to or taken seriously, they often seek out others who have the same opinions, and the current iteration of the internet where networked technology is combined with classification algorithms is perfect for helping people to find an echo chamber that validates and reflects their ideas, no matter how good or bad they may be. In our projects, our critique is directed towards people in positions of power. But in our personal relationships, when people are spreading what we know to be misinformation from our research, we try to be understanding and have a civilized conversation where we talk about sources of information and the interests at stake.”

While Going Viral is the work that deals most directly with the pandemic, it’s impossible to view the other works through any other lens. It’s clear our cultural references have been changed by Covid-19. In the second window Martin Disley’s piece Future False Positive shows AI programs attempting to “imagine” what happens when the autonomous vehicle training clips they have been watching end. The clips start off fairly ordered but quickly fall apart, streets and vehicles blurring. But it is the relative absence of people – pedestrians or drivers – that creates a feeling of foreboding that might not have been present if the piece was made a year ago. Now the AI’s attempt to categorise each vehicle and continue the sequence seems to reflect the paranoia and hyperawareness many of us feel. Like the idea that there’s so much information – and misinformation – that our minds become clogged and the way forward is, paradoxically, less clear.

Next is Dina Kelberman’s Study for Sponge Project, a time-based assemblage piece of people squeezing, massaging and destroying cleaning sponges. Again, it’s difficult to view the work without being reminded of the constant messages from governments and public health organisations that washing our hands for more than 20 seconds is one of the best defences against Covid-19. In Kelberman’s videos, which she sourced on Instagram, some people have used dyes, paint or other additives to change the colour of the water or the texture of the foam – resulting in a bright, almost kitsch aesthetic.

Kelberman was attracted to the ASMR sponge communities partly because of its incredibly niche nature and how it is a perfect example of the internet’s ability to bring like-minded people together and build communities around increasingly obscure things. “Finding the commonalities and differences among this very specific genre,” she said. “That's definitely my favourite part of the internet, even though in some ways it's the worst part and is maybe ruining everything? But obviously for some communities it's a total miracle.”

“Obviously we're on the first generation of people growing up with the internet so that will be a game-changer. It's weird because it seems like the internet has the effect both of exposing people to lots of different things, thereby making them more accepting of all kinds of stuff, and simultaneously allowing us to live inside echo-chambers where we can totally ignore other opinions and lose perspective. I don't know where it will lead but we'll probably kill our species off with global warming before the internet really runs its course anyway.”

On the next screen Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo’s piece sequencer is playing. If Kelberman’s piece is very much about the internet phenomena of right now, Hennigh-Palermo’s piece delves into the video manipulation technology of the last few decades. Her series of colourful animations have been run through several different analogue and digital video processing systems, creating an effect that feels instantly familiar – like the abstract shapes generated alongside your music in Window’s media players or videogame graphics from the arcade era.

One thing that ties both Disley and Hennigh-Palermo’s work together is a skepticism about computers and the way we seem to be putting more and more of our trust in them. Both of their pieces explore machines ‘guessing’, from Hennigh-Palermo’s synthesiers desperately trying to decode pixels that have become too low-res to be readable, to Disley’s AI trying to imagine its way out of the same few seconds of footage.

The final work in the show is by Enorê, an interdisciplinary artist from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, currently based in London. Their work is particularly beautiful in the dark, as the piece uses subtle layering techniques that are not especially clear in the harsh winter sunlight. Using videos from Google Street View and a scraping algorithm, the work is shown on two screens that sit side by side, each depicting journeys almost devoid of human life and rendered in a faint opacity, almost like watercolour paintings or coloured pencil drawings.

Every few seconds a faint message appears with the words, “Sorry, we have no imagery here”, highlighting the limitations of our current technology and emphasising the ephemeral nature of indeterminacy. Their piece – DriNing (Greater London, randomized) – was inspired by their daily commute in Rio de Janeiro and the question, “What if I could have a robot, or an algorithm, do this journey instead of myself?”.

“I came to this question about four years ago on a daily commute,” says Enorê. “There wasn't really much in it, I was just tired of the long time it took to commute and thought of that. I was looking out the window and thought of it as a frame of my journey and wondered what a machine/algorithm would see if it looked out the window in a similar situation.”

Enorê’s bot wanders through the streets of Greater London, sharing the various paths it takes through the city and its boroughs. The project allowed Enorê to explore ideas of agency and automation, and the increasing trust we are placing in algorithms and code. Like Disley’s piece, DriNing (Greater London, randomized) provides an insight into how computers see and navigate through our physical world – prompting the viewer to think about the future of self-automated cars, GPS, and city planning.

“I wanted to link to the idea of an "automated seeing". The paths, image collection and composition, and posting would be all automated,” explains Enorê. “That's how the first iteration of this work was born: I used the train lines in Rio de Janeiro as readily set journeys and made this algorithm travel through them, returning images of what it saw. At the time I was very interested in ideas relating to agency and mediated ways of seeing, so I was excited to create an algorithm that related to these questions.”

“You can think of the journey as a collection of coordinate points between the initial and final locations. The way they are calculated allows for some mathematical error, having some points fall (very) far away from it. I thought it was interesting because this ‘error’ showed up in the final images as a sort of movement — you had a sequence of images following a predictable path, and all of a sudden there was a pleasant interruption, before returning to the previous path. I enjoyed that even though I initially tried to create an accurate path between these two points, that wasn't completely possible, and I had to learn to embrace the errors.”

Underneath each work is a QR code that the viewer can use to travel online and to gain a greater appreciation of the pieces. But even those without smartphones can still marvel at the variety of work on show and the ingenuity of the human spirit even in such trying times as these. Maybe it’s time for all of us to practice embracing the errors.

Find out more about the artists here:

Derek Curry and Jennifer Gradecki, USA

Enorê, UK/Brazil

Dina Kelberman, Los Angeles

Martin Disley, Edinburgh, Scotland

Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo, NYC/Berlin

Given To Chance will run from 12 – 30 November at Nomas* Projects, 9A Ward Road, Dundee, DD1 1LP. The show is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

Project pages: