Venice Biennale 2019: If We Don’t Change Nothing Will

The Venice Biennale is one of the largest celebrations of contemporary art in the world, and this year NEoN was lucky enough to attend. As our theme this year is ‘react’ we were on the look out for politically engaged digital artwork that would really open our eyes to some of the most pertinent geopolitical issues of the present moment, and we were not disappointed.

Truly an international event, the Biennale is split across two main areas – the Giardini and the Arsenale – with smaller collateral events scattered across the city. Each area takes at least a day to traverse and entry to both the Giardini and the Arsenale is around €25.

However, one highlight was a free exhibition; Taiwan’s Shu Lea Chaeng’s multi-media installation in the Palazzo delle Prigioni – a medieval prison in the heart of the city used up until 1922. Named 3x3x6, the show explores the biographies of those incarcerated for gender or sexual dissent, including the philosopher Michel Foucault as well as contemporary cases such as Catherine Kieu (currently serving life for cutting off her husband’s penis) and live-streamer Sherry Gun, in a sort of reverse panopticon. Viewers are invited to submit videos of themselves dancing, which are then incorporated into the work. The idea being to provide an air of defiance. Philippe Shangti’s work for the Andorra pavilion strikes a similar tone, using digitally enhanced and audio-visual sculptural pieces to explore the consumerist present and the unknown future.

Another free show was provided by Scotland’s own Charlotte Prodger – winner of last year’s Turner Prize – whose single-channel film ‘SaF05’ continues the ideas of her winning entry, using footage of a maned lioness as a metaphor for queer identity and desire.

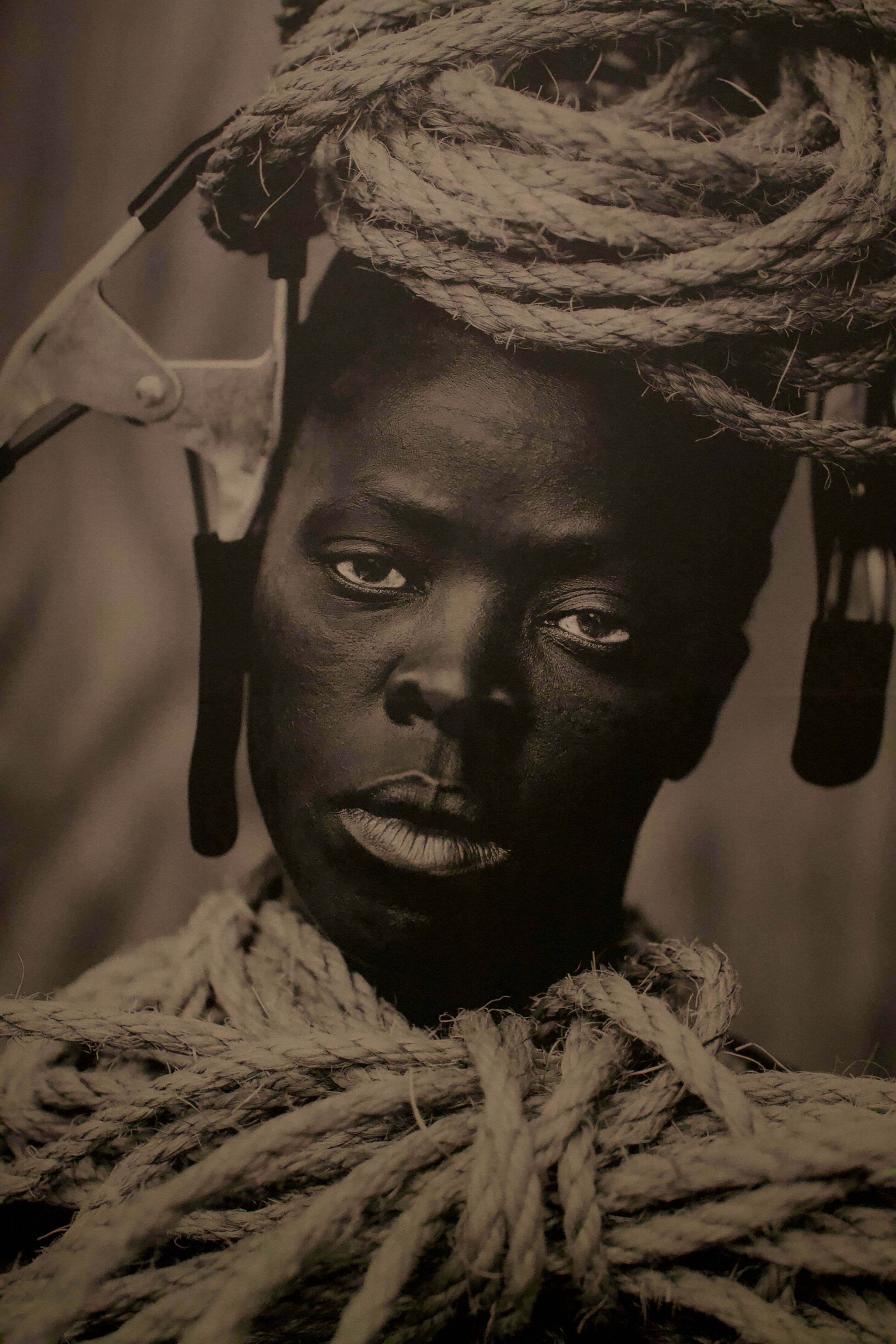

Into the main spaces, Zanele Muholi’s work stands out – especially in the Arsenale where her over-sized black and white photographs are prominently displayed. Known for her portraits of black lesbians in her home country of South Africa, for this series she turns the camera on herself and meets the viewer’s gaze with a sort of weary scepticism. It’s very powerful.

Zanele Muholi, part of the ‘Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness’ series (2012-present)

An emphasis on portraiture from artists of colour is something of a theme at this year’s Venice Biennale. Henry Taylor’s paintings dealt with the realities of black experience in the USA, referencing the Haitian revolution and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing – an act of white supremacist terrorism. Njideka Akunyili Crosby reflects on her experience of being a member of the Nigerian diaspora, while Frida Orupabo is concerned with the depiction of the black female body in art history and popular culture. While Michael Armitage’s delicate ink drawings document the political rallies leading up to the latest Kenyan general election.

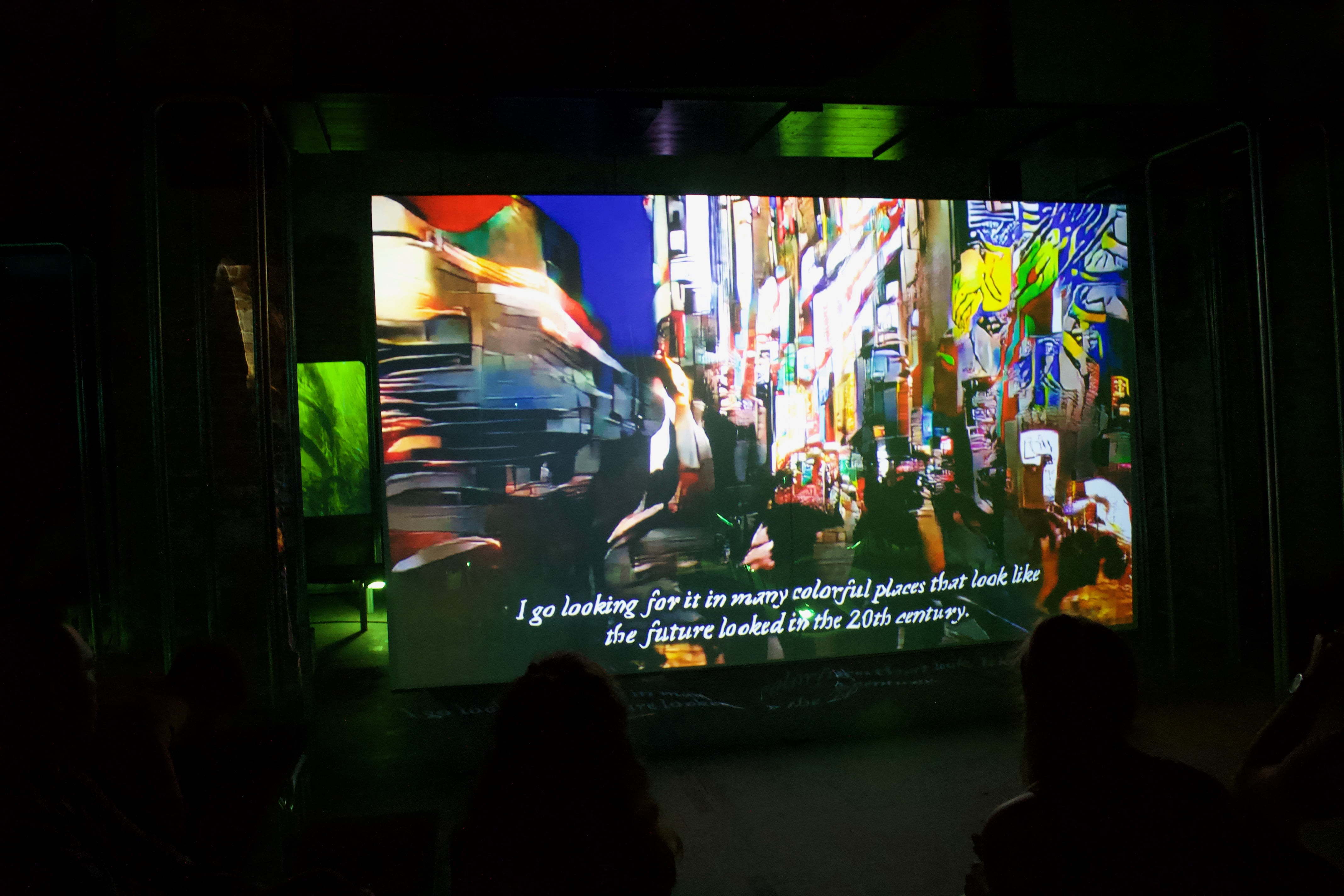

In terms of digital art, Kahlil Joseph’s piece ‘BLK NWS’ imagines a news landscape centred on intellectual black sensibility – with segments on Chester Pierce, the African-American psychiatrist that helped develop Sesame Street, and artist Noah Davis. While Tavares Strachan’s multimedia work honours Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. – the first African-American astronaut.

Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS (2018-present)

Stan Douglas’s ‘Doppelgänger’ film also featured a black protagonist – a woman named Alice, played with pathos and a sense of real horror by Dionne Audain, who is cloned in a teleportation accident. The film is randomised and looped, mirrored and doubled, creating a claustrophobic confusion for the viewer that echoes Alice’s own journey.

Science fiction films are also very prevalent at this year’s Biennale. Khyentse Norbu, a real-life Tibetan monk, uses his experience to create ‘Year 2118’ –where human beings have transcended the need to communicate using sound. Hito Steyerl’s piece ‘This is the Future’ details a woman’s search for a garden, asking whether we can trust artificial intelligence to really understand our desires. Digital flowers bloom and wither on multiple screens as the viewer walks among them on elevated metal platforms – invoking the idea of a garden while being entirely devoid of organic life (apart from the probing questions of the narrator).

Hito Steyerl’s ‘This is the Future’ (2019)

In the Danish pavilion Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind have produced ‘In Vitro’ – a two-channel Arabic language science fiction film. The protagonist Alia, by Maisa Abd Elhadi, is a clone confronting the woman who made her. An ecological disaster has made life on the surface untenable and, while a small number of adults survived, all the children perished. To preserve their memories they were cloned – leading to a situation where a generation is plagued by memories of a life they’ve never truly known – of sunlight passing through the leaves of trees, of cracked ornate tiles in old buildings, and of childhood innocence. Beautifully shot, with dialogue that hits your heart, ‘In Vitro’ is another highlight of the Biennale as a whole.

Outside of science fiction, Arthur Jafa’s film ‘The White Album’ won this year’s Golden Lion award for the best individual piece in the Biennale. Forcing white viewers to confront their own complicity, the film uses YouTube footage from ‘ex-racist’ Dixon White, interspersed with soundbites from white supremacist and mass murderer Dylann Roof, Honey Boo Boo, musician Erykah Badu, O.J. Simpson, and many more. It’s uncomfortable viewing, as is Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s film ‘Walled Unwalled’. A monologue on how sound travels through walls, the piece explores the murder of Reeva Steenkamp by Oscar Pistorius and the significance of radio stations in West and East Berlin during the Cold War.

In terms of sound pieces, Shilpa Gupta’s installation ‘For, in your tongue, I cannot fit’ features the work of 100 poets who were imprisoned for their work or political positions. Print outs of their poems are stuck on floor mounted spikes, while reverse-wired microphones hover above them broadcasting their words. The poems are read in multiple languages, creating an experience of disorientation as the viewer hears snippets of their own tongue before lapsing back into incomprehension.

Alban Muja’s video installation ‘Family Album’ for the Republic of Kosovo pavilion also deals with memorialisation – seeking out the child subjects of famous photographs of the Kosovo War, the subsequent interviews cover the impact the war and the photographs had on their childhoods, as they reflect on ideas of representation and the role of the media in covering foreign conflicts.

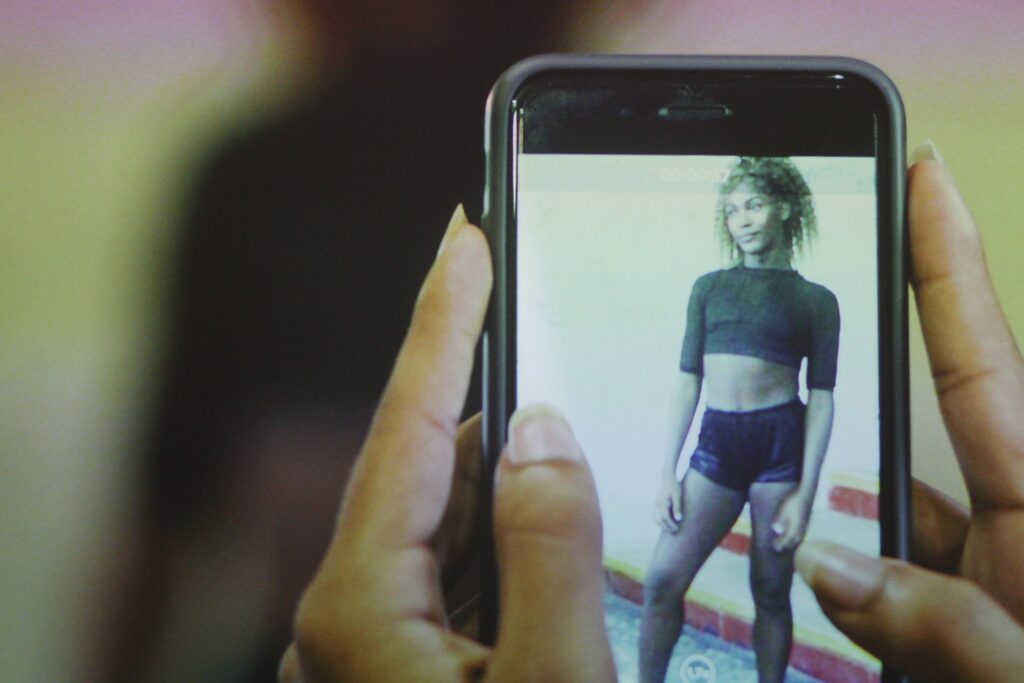

Finally, a special mention should go to the Brazilian pavilion. Their piece ‘Swinguerra’ by Barbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca explores dance as form of political resistance. While there are tender moments, such as dancers smoking in a stairwell, the majority of the film is a celebration of the human body. It’s vibrant and intoxicating and a refreshing antidote to some of the more pessimistic pieces on show at the Beinnale.

‘Swinguerra’ by Barbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca (2019)

Overall, our favourite pieces at this year’s Venice Biennale were ones that challenged and enthralled us, that shone a light on the inherent racism of the art establishment and forced us to think about what the future of humanity holds. And if you want to see the work for yourself you have until 24 November. Book your tickets here – labiennale.vivaticket.it.