Thinking about feminist leadership

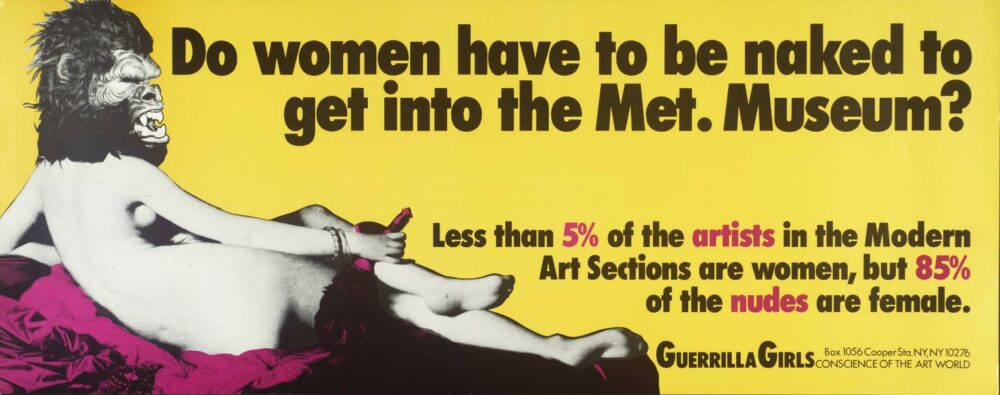

At NEoN, we’ve been thinking about the role and representation of women and non-binary artists in the digital arts. As a women-led organisation, championing women's work since our inception, we want to be setting the best example of feminist leadership. As part of that aim, we asked our network what “good feminist leadership” means to them and below, we’ve consolidated and unpacked some of the responses we received. “Leadership to me is as much about listening and learning from others as it is about dissemination and education,” explained NEoN co-founder Clare Brennan, identifying some of the key qualities of a good feminist leader as; “knowledge, determination and, above all, compassion”. She said, “It is no secret that women have been under-represented in the arts for centuries, and the digital arts sector is sadly no different. Art, science, politics, sport... everything should reflect and represent the true make-up of our society and the myriad of voices within it.” In the general population, women slightly outnumber men. While this is reflected in the visual arts, work by the Scottish Contemporary Arts Network (SCAN) and Creative Scotland has shown that men in the visual arts consistently earn more than their female counterparts. SCAN’s ‘Mapping the Visual Arts in Scotland’ survey of 2015 found that women were earning on average 56% less than men for those in full-time work. The ‘Understanding Diversity In The Arts Survey Summary Report’ by Creative Scotland in 2017 found that 44% of women felt that their gender had been a barrier to their career progression, with men more likely to work in senior roles, to earn more, and to describe their work as having an international reach. The report attributed this discrepancy to many factors, including that women are more likely to be the primary or sole carer of children and be working part-time. One of the barriers highlighted was the lack of female role models in senior or leadership roles. “In a sphere so usually dominated by one gender, feminist leadership within the arts (especially the digital arts which are arguably even more dominated), is integral,” explains artist and curator Elizabeth Ann Day, who worked with NEoN while serving on the committee at Generator Projects and who recently founded Volk Gallery and Windfall* magazine with Luke Greer. She added, “If the sector is to be seen, and actually function as an equal field, then feminist leaders, focussed on equilibrium, must exist.” One of the most recent reports on diversity in the Scottish arts, the Scottish Artists Union’s ‘Membership Survey’ of 2018, found that gender was the most frequently reported barrier to equality amongst their members. They reported, “While one member noted that there had been significant improvements in relation to gender, largely due to more women working in the sector and actively supporting each other, others suggested that there is still inherent sexism within the sector.” “Related to this, some members identified continued societal expectations for women to also run a house and take on caring responsibilities often impacting on their practice, and the fact that there are still experiences of a gender pay gap. One also talked of the ‘slightly sexist attitudes regarding female painters - that their work ought to be more “comfortable”.’” “We're still at a stage where we need to actively fight and promote voices of women to encourage future generations to have the confidence to step up and step forward,” says Brennan. “I’m still learning about ways in which women have consistently and systematically been written out or played down in their contributions to society and culture throughout history. I continue to see women going uncredited/under-credited/overlooked for their pivotal roles or skills in collaborative projects. And it's unequivocally worse for women of colour.” She points to the example of the Guerrilla Girls, a group of anonymous women artists who protested the lack of female representation in the arts. “I remember watching them on the Late Show where they spoke about how every aesthetic decision has a value behind it, and if all these decisions are being made by the same kind of people, then the art will never really look like the whole of our culture,” says Brennan, paraphrasing the Guerilla Girls perspective. “Predominately, art collectors on museum boards have been white, middle-class men who buy art made by other white men… In which case then, the Guerrilla Girls say, it's not really a history of art that we’re seeing when we visit these collections; it’s a history of power.” One of the most famous of the Guerrilla Girls campaigns is a large poster of a nude white woman reclining – based on the painting ‘La Grande Odalisque’ by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The woman wears a guerrilla mask and faces the words, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the Modern Art Sections artists are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.”

Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? 1989 Guerrilla Girls http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/P78793

But what makes a good leader and role model? Is it enough to merely be in the position, or must women in management and leadership roles be consciously feminist in their approach? Empowering women and raising them up to leadership positions has long been recognised as one of the core routes out of poverty for communities across the globe. To that end, anti-poverty organisation ActionAid has developed Ten Principles of Feminist Leadership. These principles are; self-awareness, self-care & caring for others, dismantling bias, inclusion, sharing power, responsible & transparent use of power, accountable collaboration, respectful feedback, courage, and zero tolerance of discrimination and abuses of power. While these principles are not sector-specific, they reflect how NEoN co-curator Laura Leuzzi answered our question, “What does good feminist leadership look like to you?” She said, “Lead with a view to represent the oppressed and marginalised, support and lift others - especially those who are in need. Inspire and stimulate cultural and spiritual growth in society at large.” She added, “I feel feminist leadership is essential in every field, but in the arts, it is particularly pivotal because women artists have always been marginalised and under-represented. For new media, it’s particularly true that women have been excluded from mainstream museums, events, and the commercial system in many occurrences. Looking at Scotland, during this COVID-19 crisis, I particularly admired the DCA Director, Beth Bate, for how she spoke to the media about the challenges that the sector is facing and how she has listened to the feedback of the city, her audience, as well as her staff.” Beth Bate credits taking part in the Clore Leadership Programme as being pivotal in her journey towards the directorship of Dundee Contemporary Arts, saying in an interview with The National soon after her appointment that, “It was taking part in the Clore programme that allowed me to take the next step in my career. It also allowed me to be able to talk a lot more open about what I wanted to do, which can sometimes be quite difficult for women.” Before joining the DCA, Bate launched the Great North Run's cultural arm – spending eleven years building it into a successful complement to the famous half marathon. In her role, she commissions works by artists such as Jane and Louise Wilson and Mark Wallinger. But of ActionAid’s Principles of Feminist Leadership, it is in the act of stepping away from this role to take on the challenges of somewhere new that shows courage, self-awareness and a commitment to sharing power. Another woman who benefited from the Clore Leadership Programme, which provides training and development opportunities for cultural sector professionals, is Adele Patrick of Glasgow Women’s Library – whose resulting paper ‘Feminist Leadership: how naming and claiming the F word can lead the cultural sector out of equalities “stuckness”’ is essential reading for those in the Scottish arts community. Within the paper, Patrick engages with some of the problems detailed above, arguing that the “rudderless” cultural arts sector often fails to achieve it’s diversity and inclusion goals and can often be guilty of falling back on promoting the work of middle-class white (and often dead) men. She highlights the importance of thinking critically about the “feminist” part of “feminist leadership”, saying, “It is high time to recognise that not only has feminism the radical chops to bring to the crisis represented by the stalled state of the equalities agenda in the cultural sector but that feminist leadership, needs to be acknowledged, named and claimed in the process.” Patrick identifies part of the problem as a lack of knowledge of the most impactful methods of addressing inequality among potential women leaders and those already in power positions. She suggests that intersectional feminist leadership has certain qualities, including being focused on open dialogue, being collaborative and inclusive, emphasising empathy, and being unafraid to take risks or innovate. She writes, “In contrast to the monolithic and ‘stuck’, the calcified, unfit for purpose hierarchical models that still characterise the mainstream, feminist led organisations are mobile, heterogeneous in makeup, are to be found in an array of manifestations and forms across the world, are tailored to specific contexts cultures, communities and constituencies.” Day echoes some of these points – emphasising the importance of dismantling bias, promoting inclusion, and sharing power. She identifies a feminist leader as “someone with a clear drive to make their workplace or project more accessible and balanced”. She urges women in leadership roles to “assess your privilege”. Holding truth to power is another way women can be inspiring leaders, particularly in the field of politics. Many of the USA’s leading female politicians have become household names in Scotland, including the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg, associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton, Vice-President Kamala Harris, and congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez part of an informal group of influential Democratic members of the U.S. House of Representatives known as The Squad, along with Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley and Rashida Tlaib. Having women in such positions of power allows other women and girls to reconsider what is possible in their own lives and situations, inspiring them to reach similar positions themselves – even if the role models are in another country or industry. Leuzzi says, “Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is one of the global feminist leaders that I admire the most. She is aware of the challenges, the potential, and pitfalls of Social Media, A.I., etc., and she is not afraid to question the system and meaningfully contribute to public debate and lawmaking. At Zuckerberg's Senate hearing in 2019, she was one of the few who asked the right questions and did not budge.” Taking another of ActionAid’s Ten Principles of Feminist Leadership, women are often seen as bringing a higher level of collaboration and networking to their industries. Organisations such as Women in Tech use role model programmes, pitching classes, scholarships, accelerator programmes and many other approaches to support and encourage women and girls. Other organisations have sprung up that offer mentoring support, such as Digital Women Leaders and Coaching For Women In Film. Women-only networking events have also risen in popularity. There are also small practical steps that leaders can take to ensure workplaces are women-friendly, like providing free sanitary products in the workplace bathrooms. Other considerations could be on-site childcare, domestic violence leave, flexible working or job-sharing, bereavement leave in cases of miscarriage, and ensuring that female employees have adequate support and training. For Brennan, when looking for examples of feminist leadership, its activist and academic Angela Davis that springs to mind, particularly her quote, “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time,” said during a 2014 lecture at Southern Illinois University. Brennan explained, “Angela Davis is incredible in the way she highlights the intersectionality of gender, race and class, and the impact this has on real lives. Her resilience and tenacity are an inspiration. She is 76 now and is still fighting the good fight.” In terms of advice for women in leadership roles, both Brennan and Leuzzi stressed the importance of listening. “Continuing to listen, learn, read, ask questions, challenge norms, and demand change is essential,” said Brennan. “A tide is turning though, and we see hope in young female figures who are showing us the way, all across the globe.” Leuzzi added, “Listen. Listen to others' needs, requests, feedback. Keep an open mind and be open to change your mind. And do not be afraid to admit you are not perfect. Everyone fails. It is what makes us human.” Written By Ana Hine Feature Image Credit: ActionAid's Ten Principles of Feminist Leadership