Olia Lialina discusses the lost internet platform

Olia Lialina is considered one of the first people to use the internet as an artform with her piece My Boyfriend Came Back from the War from 1996. For NEoN she will be displaying a collection of works resulting from her ongoing excavation of the Geocities Torrent – a massive archive of pages from the lost internet platform. NEoN blogger Ana Hine caught up with Olia to talk about the project.

Do you prefer the aesthetic of the internet of the 1990s over the 2000s and the 2010s? What are the most significant changes, in your opinion, between these internet eras?

I can’t think about web aesthetics in decades. In the 1990s one astronomical year was ten on the web. If you read David Siegel‘s legendary design manual “Creating Killer Websites”, you will be amazed that already in 1996 he talks about the third generation of web design. Things were always changing fast, aesthetically and ideologically. In 2012 my students made a fictional timeline, that – in many little steps – shows the development of the web aesthetics. Significant change is not in aesthetics, but in the structure. There is no place for personal web, there are no “home pages” anymore.

What was Geocities, and what was its significance to you personally?

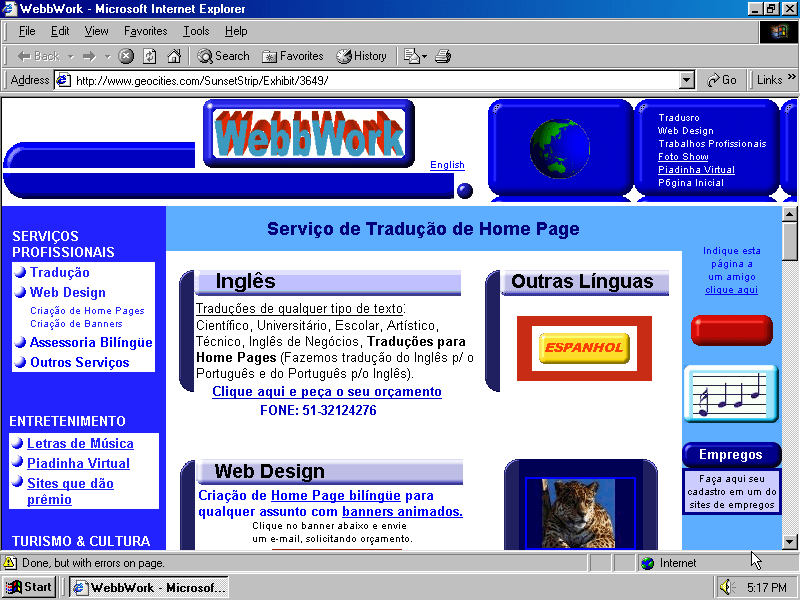

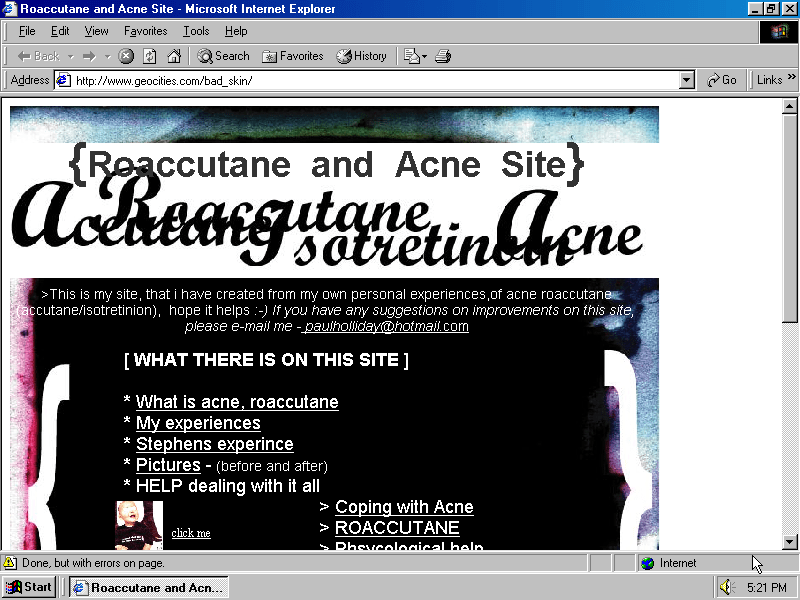

Like everyone who didn’t have a page on Geocities in the second part of the 1990’s, I was very sceptical about this free hosting service. I thought about it as an outlet for people who have too much time and too little understanding of how to make web pages correctly. But around the turn of the century when I noticed how fast self-made things disappear, I changed my mind and started to pay closer attention to amateur production. I developed an understanding and respect for, not only Geocities, of course, but vernacular web outside of it as well. Today we mostly talk about Geocities because it as the only substantial archive of self-made web pages.

The One Terabyte of Kilobyte Age project seems to revel in the Geocities pages that were saved without discrimination. How do you measure value in a context like this?

I don’t. There is value in all of them. I learn something from every page I see. I categorize, and tag, make conceptual and formal connections, collect more and more material. Of course not all 400k websites in the archive are interesting on their own, but each adds something to our understanding of what it means to be a web master of your own site.

Why is digital archaeology important?

Every archaeological work is important. Evacuating the history of the world wide web is important for deeper understanding of this beautiful and powerful medium. It is important for educating web users about the power they can have.

What do you think digital archaeology will look like in the future? Would you be involved in projects to save Myspace profiles or Tweets, or was there something unique to Geocities that persuaded you to work on archiving it?

Social networks are another story, because of their scale. The Geocities archive is 1TB, whereas the Dutch social network Hyves, which closed in 2013, is 25TB. Global players like Twitter or Facebook would be in Petabytes. But size is in fact the smallest issue. Their structure and, let me say, philosophy are the issues that would make classic archiving useless. We should learn already now to deal with them on another level: a low level, a personal level. If we make a little archive, we can create little stories that will tell our stories in the future. For example recording your own interactions or whatever you personally, or as institution, through something like webrecorder.io. I also think there must be an understanding that nothing will stay there forever, we are always on the eve of this or that service being closed and we should act accordingly.

Do you have favourite pages that have been saved?

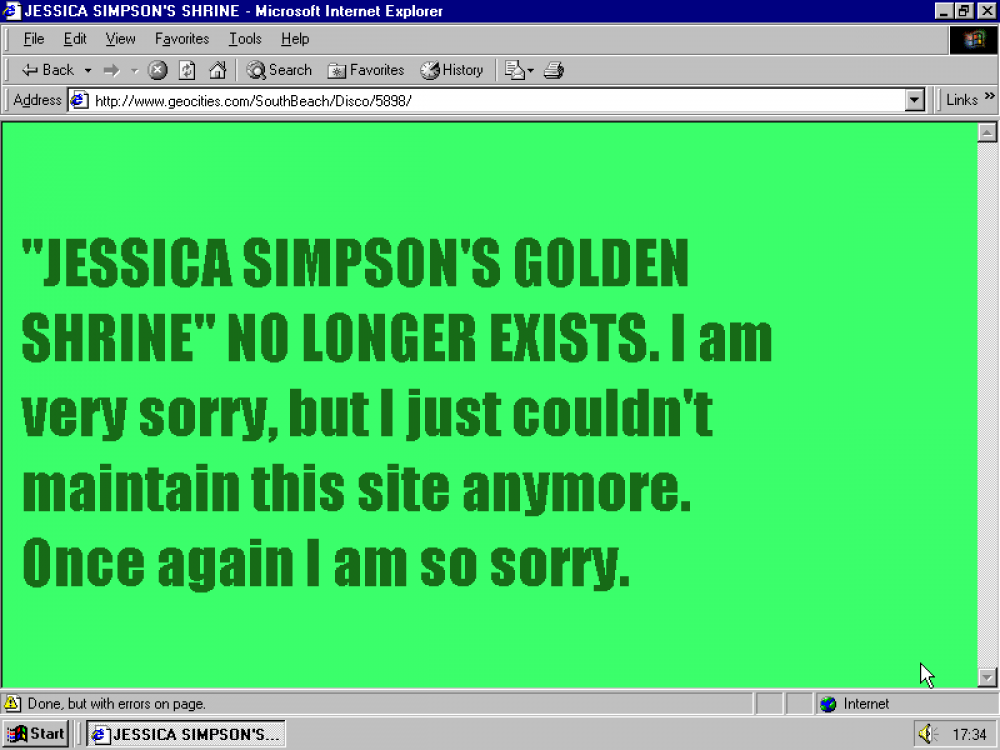

I do. These are two types of pages I like and both are those that are not very spectacular visually, but precious content-wise in the context of the archive. First are pages that give a promise to be complete, to become the greatest on the web, in a week or two. Second are pages that announce their own death. I often see them next to each other, and it is quite dramatic. At the festival I will show them as two parallel slide projections called “Give Me Time/This Page Is No More, with hope on the left and despair on the right. I hope you spend some time sitting in between, watching.

Interview by Ana Hine