Given To Chance: exploring indeterminacy and sharing (despite the pandemic)

The on-going Covid-19 pandemic has caused a shift in presenting artworks – with an ever-increasing emphasis on street and public art. In this context the next show at Nomas* Projects in Dundee, Given To Chance, is well placed. The gallery space consists of five windows that look out onto the busy Ward Road in the city’s centre. This set-up allows 24-hour access to the works, perfect for social distancing.

A collaborative project between NEoN Digital Arts and the AHRC-funded research project The Future of Indeterminacy: Datification, Memory, Bio-Politics at The University of Dundee, Given To Chance explores the dual themes of indeterminacy and share and features the work of four artists and one artistic duo: Dina Kelberman, Jennifer Gradecki and Derek Curry, Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo, Martin Disley, and Enorê.

For Natasha Lushetich, professor of Contemporary Art and Theory at The University of Dundee and project lead, the theme of indeterminacy in particular is a loaded one, drawing on the western scientific tradition and the work of physicists and mathematicians, Indigenous scientific and cultural narratives, religious philosophies, and artistic movements like Fluxus, Obfuscation and Dirty New Media.

She says, “With acceleration, the proliferation of digital technologies, and the use of algorithms in almost every sphere of life (health, traffic, finance, education, etc), we’re faced both with permanent (and often unwelcome) change and the over-determinism of algorithmic governance. This is why it’s important to take another look at indeterminacy in all senses of the word.”

For Joseph DeLappe, NEoN’s co-curator for the show alongside Laura Leuzzi, both themes have been an important part of his practice as an artist and of his thinking as an academic. DeLappe, a professor of Games and Tactical Media at Abertay University, said: “To me it is about accepting and embracing chance, or perhaps making “chance” and hence change happen through the making and sharing of art. All the works in the show somehow do this.”

“I think what made these artists stand out is that they were interesting ideas for works that would generally have lives outside of the window display context of Nomas*, but at the same time be visually striking and make for a strong group exhibition. The commonality that has emerged from our choices are in that all the works will be shown on screens – these are all time-based documents of works that are generally not simply video works but artifacts of various technological and conceptual strategies by the artists. We did see several proposals from artists who were specifically addressing issues surrounding the pandemic. Enore’s work of virtual wanderings of London likely most reflects this sensibility.”

Leuzzi curated last year’s NEoN show at Nomas* Projects and expressed relief at already knowing the space and its challenges – though she was clear that all necessary guidelines and precautions would be taken during the installation and deinstallation of the show.

“I think this pandemic has deeply affected everyone, with no exclusion in our society, including artists, curators, organisations,” she said. “The concepts of indeterminacy and sharing are key to understanding our time and I think that the works of the artists will help unpack how they manifest and how we perceive them from different perspectives.”

One of the participating artists is new mother Dina Kelberman, who initially found the pandemic and subsequent lockdown freeing. “Honestly at first the pandemic was GREAT for me making art,” she said. “I finally felt like I had enough time to spend on things, which is weird because my day to day life actually changed very little. But some kind of weight of life expectations was lifted and it was so freeing and I produced a lot and felt great. But I was pregnant and now I have a baby, so that’s the opposite. My actual work was already very solitary, stay at home, internetty, so the pandemic has mostly affected me emotionally, as it’s affected everyone, and not so much my lifestyle or the way I work.”

Her contribution, Study for Sponge Project, is a time-based assemblage piece exploring the internet phenomenon of Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) videos – in this case specifically the ones of people squeezing, massaging and destroying cleaning sponges.

“The Indeterminacy call immediately resonated with me and made me think about this project from the first sentence about ‘connections and commonalities between sharing and indeterminacy’,” she explains. “So much of what interests me in this project and my work in general is looking at this phenomenon of large quantities of media being made by hundreds of different people that are really specific to a particular esoteric online community, and then analyzing the intentional and unintentional formal qualities of that media.”

Initially Kelberman was interested in YouTube fetish videos, particularly the way they circumnavigated the strict anti-pornography rules on the site. This led her to Instagram and ASMR, where even something as initially innocuous as a cleaning sponge being wrung can have a sexually suggestive element. “When I first came across these sponge videos I was instantly in love,” she said. “They’re so simple and tactile and sponges are beautiful to begin with, and I love images of hands, so it really had it all. I actually hate ASMR sounds like whispering and scratching but the sponge sounds didn’t annoy me the same way so that’s a bonus. Also I definitely think people are jerking off to these.”

Kelberman started separating the videos into two broad categories; the “good” and the “evil” and producing a piece of work where one blends into the other. Although sound is often a major component of ASMR, the design of the Nomas* exhibition space – with its window-based set up – means that her piece will be soundless, though she doesn’t see this as too much of a problem.

“I’m interested in how different this piece is with and without sound,” she explains. “I’m a very visual person so that’s just what grabs me more. But I also think there’s something to the imagination element of the piece when you can’t hear the sound, you kind of fill in what you imagine the sounds might be, or a sound that wouldn’t necessarily be realistic but would be fitting. When I look at the abrasive videos I imagine screaming. For me the sets of videos are really peaceful and comforting and then really creepy and disturbing. Apparently other people find them ALL creepy and disturbing. I don’t really set out to evoke a response in particular because for me what’s interesting about art is how different people respond to the same thing.”

Fellow participating artist Sarah Groff Hennigh-Palermo is more keen to evoke a particular emotional response. She identifies as a “lost Californian”, having left as a teenager to pursue higher education. Her early years influence her palette though, with the colours and shapes being reminiscent of a youth under the harsh West Coast sun. She explains, “When I think of my childhood, it’s always the light that comes first. Light in outdoor pools, the relentless sun, the brightness of it always. Just a dazzling bright transcendence. The way an Agnes Martin painting can make the desert palpable, I want people to be able to see the light in swimming pools and mall video displays in my work. I believe that if I can gather up these feelings into a video and show them to you, you can feel the same things, even if your references are different because the longing comes through and you also feel longing.”

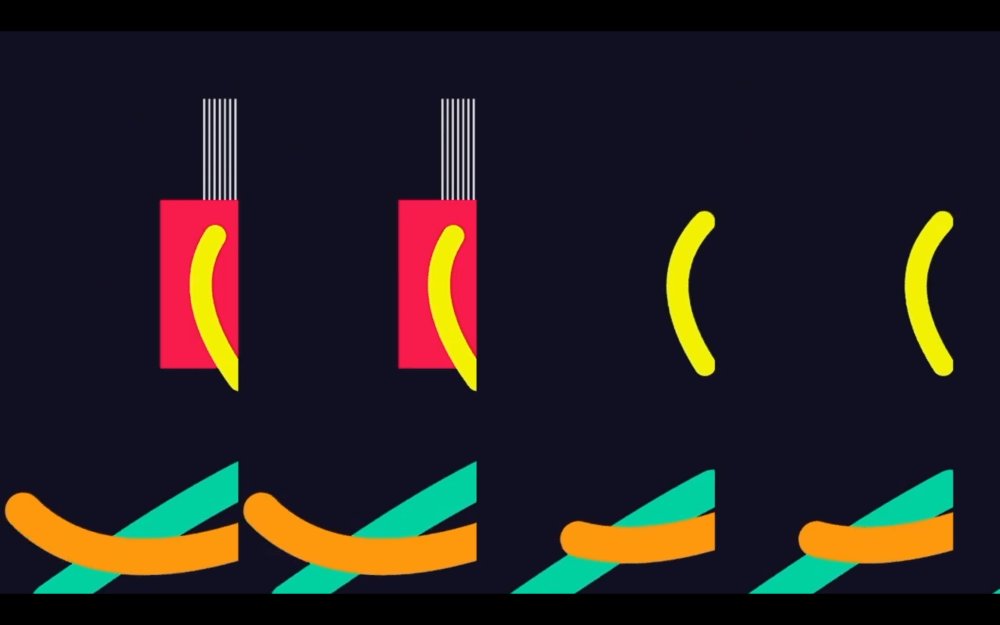

Her work, sequencer, is a series of three short silent animation works which she has run through several analogue and emulated video processing systems to create an aesthetic quality she calls “fuzz”.

“I think of fuzz as the evidence of indeterminacy and imperfection,” Hennigh-Palermo explains, “A fuzzy image is an image that has been processed through different technologies and resolutions, and in this process information has been lost and then reimagined. When a 1920 x 1080 image is rescanned by an analogue camera or converted to an analogue signal by other means; fed through frame buffers and synthesizers with much lower resolutions; and then re-digitized, the image gets soft edges and bits of colour flowing over what were once hard edges. This is because the process loses the knowledge of definitely what each pixel should be and has to guess, and it guesses wrong. That’s what computers are doing with all of our information — guessing and guessing wrong.”

An interest in livecoding and experimentation with a web-based video synth system called Hydra led Hennigh-Palermo to the Fairlight CVI, a video synth and effects system from the 1980s. Last year she undertook a residency at the Institute for Electronic Arts at Alfred University, applying partly so she could use their Fairlight.

“I had always felt that the images I generated would be better if they had more of the fuzz and soft edges,” she said. “I had hopes the Fairlight would help me get some of that. And it did! The second day I was there, I got the system set up to rescan footage from my laptop and the moment I saw it, I knew it was what I needed. It gave me the capability for deeper layers and warmer tones and for narratives I wasn’t able to render just with my little system.”

She now owns her own Fairlight, though it is with her mother in LA. The global pandemic has forced Hennigh-Palermo to “hunker down” with her husband in Berlin, preventing her from picking up her beloved piece of kit and, sadly, from seeing Given To Chance in person.

She said, “In terms of my practice, the effect has been less traveling + fewer friends in this city = more time to focus. I think it’s the silver lining of the pandemic for me. Although if the Fairlight I bought wasn’t stuck at my mom’s place in LA, it would be even better. But it’s old and delicate, so I don’t want to ship it. I’d rather carry it on a plane myself.”

“The more people you come into contact with, the more risk you encounter and diffuse. I don’t want to get sick, and I really don’t want to spread the virus to someone immunocompromised. I have always had a wonderful time visiting Scotland — it’s one of my favourite places — so I’m extra sad it’s not really possible.”

Edinburgh-based Martin Disley is hoping to be able to pop-through for a visit though, lockdowns permitting. His piece Future False Positive tackles the problem of artificial creativity from another angle. “The problem is found in every application of generative/predictive artificial intelligence, ‘creativity’ is just one sphere application it would be present in,” he explains. “Others might be autonomous vehicles, predictive policing, data-driven policy etc… anywhere an autonomous decision is being made. A machine learning algorithm cannot create something it has not already seen. The more these systems govern our lives, the further limited the spheres where something truly new can manifest”.

“We think of them as nothing but math, and that somehow math is neutral. We should think about them as a tools that have limited appropriate uses. They are becoming the dominant epistemic mode of our time, by which I mean they’re becoming the way we learn and think about the world.”

The resultant single channel HD video is deceptively simple, showing cars driving down roads as captured by autonomous vehicle training clips. These clips are normally fed into AI programs to train them to recognise and categorise vehicles, improving technology such as speed cameras. But Disley has instructed six generative neural networks to ‘imagine’ what happens after each training clip ends. So, as you watch, something odd happens; it starts to become clear that the cars and streets you’re seeing are no longer real, in the sense that they do not correspond with any streets on our road maps or cars in our car registration databases. Instead Disley’s intention is to demonstrate the limitations of machine learning systems and to warn us of a possible future – one where possibility is limited by the inability of our technological systems to imagine new and novel scenarios.

In terms of the pandemic, Disley describes himself as “lucky” saying, “I had some long-term projects which were essentially unaffected and my work can usually be presented digitally so I was somewhat protected in that sense.” While he’s been disappointed with the majority of “virtual” exhibitions he’s seen, and had some of his own physical exhibitions postponed, he expressed excitement about Given To Chance, saying, “I was excited by what the Indeterminacy groups sees as the liberatory potential of indeterminacy and I was moved to attempt to render what is a stake (a world without it).”

Given To Chance will run from 12 – 30 November at Nomas* Projects, 9A Ward Road, Dundee, DD1 1LP. The show is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

As part of the wider Future of Indeterminacy programme a series of virtual workshops and artists talks will be taking place online, with the first one on 6 November featuring Kuai Shen, Sha Xin Wei & Emiddio Vasquez. More details here

Article by Ana Hine