Bread, Roses, Coal, Water and the Ecosexual Position

Galen, a physician in ancient Rome, has been credited in attesting that “bread is food for the body, but flowers are food for the mind.” A version of Galen’s claim became a trade unionist call to action and reflection in the early 20th Century. The assertion that there must be “Bread for all, and roses too” was popularised in speeches by North American trade unionist suffragettes, Helen Todd and Rose Schneiderman, poet James Oppenheim, as well as banner slogans and chants from the striking textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts (1912). What may have been lost over time is that the roses stand for wellbeing, beauty and joy. Now, as then, the trade union fight is for the collective improvement in the quality of our lives, one which goes beyond existence and basic subsistence. The collective fight is one of hope, now and in the future. In 2021, as the bleakness of multiple forms of climate catastrophe and the reality of living through a pandemic unfold, hope is wearing thin. There is a slow recognition that the fossil fuels, nuclear, mining and weapons industries have caused permanent destruction and contamination to land and water across the Earth. The lives which many of us have been so used to knowing and living, rely on the exploitation, displacement and harm of human and non-human lives. In these realities, ways of knowing, and living, seldom recognise the benefits of a nourishing and nourished society, one which sustains collective care, wellbeing and joy, unless presented by institutions and industries interested only in profit. Despite Western societies becoming richer, the people have become no happier and the causes of anger, dissatisfaction, exhaustion and alienation amongst us are rarely addressed. Every fibre of our being is mechanically processed as payment and/or profit. Our (restricted) movements, be they organised demonstrations of collective disaffection or those movements which require the leaving behind of your sense of belonging, are also sources of profit. Where is our replenishment? Where is our rejuvenation? Where is the re-collection of who we are to each other and what our responsibility is in the world? We keep searching and looking for healing spaces, to keep from being destroyed. Those who are not (yet) dead have to go on. Is it any wonder those who are living are now experiencing grief? The problem is, if humans become consumed by grief, we lose our ability to experience joy and this drains our capacity to keep fighting for climate, environmental and social justice. Perhaps artists and writers can bring some insights and hope into the picture. When navigating and pushing back against oppressive colonial violence, Cree poet Dr Billy-Ray Belcourt attests that “Joy is art is an ethics of resistance”. And in their latest book, Assuming the Ecosexual Position: The Earth As Lover, Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle draw attention to the practice of Argentinian artist and activist Roberto Jacoby, “who advocated for what he called “strategies of joy”: small actions that face down and confront the fear in people’s minds.”

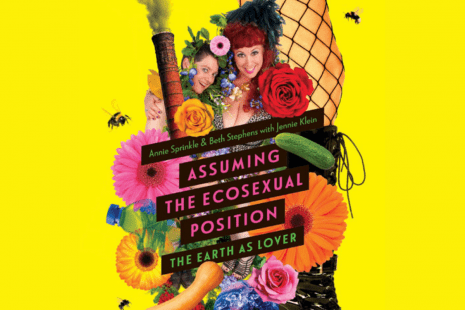

Photo credit Julian Cash and Design Credit Sandra Friesen

Collaborative environmental activist artists, Professor Beth Stephens and Dr Annie Sprinkle root their (19 years) relationship with each other, nature and their activist communities in “strategies of joy.” Their current exhibition, Assuming the Ecosexual Position, was featured in Wired Women, Dundee’s NEoN Festival 2021. This exhibition has been shown online (in NEoN’s virtual gallery space) and is currently showing at Sharing Not Hoarding, an established public art site, until January 16th, 2022. For many years, NEoN Digital Arts have presented visual art festivals, academic symposia and pop-up art events that are temporarily embedded into Dundee’s city landscape; using locations such as public buildings, shopping malls, and gallery spaces.

Photo credit: Kathryn Rattray

The Assuming the Ecosexual Position exhibition, at Sharing Not Hoarding, is a series of 18 large-format posters situated on painted wooden hoardings along S Castle Street (near Dundee’swaterfront). These highly colourful exhibition posters are camp and mischievous digital photocollages, packed with innuendo. Along with some newly created works, the posters depict images from Stephens and Sprinkle’s Love Art Laboratory projects, E.A.R.T.H Laboratory (UCSC), theatre shows and films, and their new book, Assuming the Ecosexual Position: The Earth As Lover. They include wedding photos from their marriages to the Sea, the Snow, the Rocks and the Earth, as well as the Ecosexual Manifesto, and a gorgeously illustrated how-to list of 25 Ways to Make Love to The Earth. Since Sharing Not Hoarding is just opposite Dundee Urban Orchard’s Edible Garden, in Slessor Gardens, it is the perfect site for this particular show (though the fruit will be eaten by now). The Assuming the Ecosexual Position posters can be easily viewed from a distance, drawing a broad range of publics who frequent the park. The exhibition can even be seen by the security camera persons, but the primary audience at this site are a mix of passing pedestrians. Naya Jones and Lioba Hirsch’s intervention, Incontestable: Imagining possibilities through intimate black geographies posits geography as a (post)colonial discipline, one shaped by what whiteness sees, understands, and relates to Black geographies. Last year, Sekai Machache’s exhibition a BREAdTH apart (part of the Scottish Black Lives Matter Mural Trail) was located at Sharing Not Hoarding. The art show featured 16 portraits of Black people in Scotland wearing facemasks made of African cloth and was created “to bring forward ideas about the visibility of black people in Scotland, and about our vulnerability to Covid-19”. The works also highlighted narratives surrounding Covid-19, which continue the biologising and pathologising of Blackness and race. Shortly after the portraits were put up, they were vandalized. As Jones and Hirsch assert, “anti-blackness is incontournable and upholds the resistance–struggle–resilience discourse, which Black knowledge and lives are unable to move beyond, and eventually disappear into”.

Photo credit: Sekai Machache

Like Black geographies, which can offer versatility, creativity, and freedom to present the possibilities of Black life, knowledge production and futures against and beyond resistance to anti-blackness, artworks too can become entry points into conversations that some people may have previously felt excluded. Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle use humour and sexy high camp as a hook into what artists Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison call a “conversational drift” where all parties are invited into the conversation to appreciate the whole picture. The inclusive approach of “conversational drift” was especially important when Stephens and Sprinkle made their films Goodbye Gauley Mountain: An Ecosexual Love Story and Water Makes Us Wet: An Ecosexual Adventure. NEoN screened Water Makes Us Wet during the online portion of this year’s festival, followed by a filmmakers Q&A with guest curator Ailie Rutherford. In Water Makes Us Wet, the artists tour the lakes, rivers, watersheds, ocean beaches, and wastewater facilities of California. In addition to showing the work of wildlife biologists who are protecting the watersheds, they highlight the damaging consequences of corporate water extraction and exploitation by Nestlé. Their first collaborative film Goodbye Gauley Mountain also focuses on corporate exploitation and extraction. It became Beth’s Ph.D. project; a personal activist film that exposed the callous ecological devastation occurring in Appalachia. When Beth Stephens was growing up in West Virginia, the Appalachian Mountain range was a pristine and complex ecosystem. However, because of the shift from conventional coal mining to Mountain Top Removal (MTR) (that literally blows up the tops of the mountains to access coal) the aerial photograph of Appalachia now shows a different picture. Trees, plants, watersheds, water supplies and lives are all being ruined to supply cheap energy to the big cities. Goodbye Gauley Mountain concludes with Beth and Annie’s wedding ceremony to the Appalachian Mountains. Imagine if the Trossachs hills had coal seams running through the summits. Would Scotland have been supplying cheap MTR coal to energy-hungry London? What would Glasgow have done for water supply if Loch Katrine or Loch Lomond had been poisoned from the toxic run-off from the open strip mines on Ben A’an, Ben Ledi, and Ben Lomond? If you think that this couldn’t have happened in Scotland, look at the satellite picture of the “House of Water” coal strip/surface mine near Logan, in Ayrshire. When a nation has signed up to Free Trade Agreements like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA, now called the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement CUSMA) there is almost no recourse of action against multinational corporations that destroy entire ecosystems like the Appalachian Mountain range. From our perspective in Scotland, we should all be paying attention to the details in the Free Trade Agreements that are being signed in post-Brexit UK. In the latest developments on climate action, it remains to be seen if the new USA – China coal decommissioning agreement at Cop26 will be implemented soon enough to stop further damage to Appalachia. Technology is often considered a hopeful solution to varying problems, from social justice, our climate crisis and even, the pandemic. However, we are living in an age of complex contradictions. Throughout the pandemic, many people living with disabilities and/or chronic illness gained more access to cultural events, as did people who might not feel comfortable entering and being in arts and cultural centres, museums and theatre spaces. For people with access to the internet, the many (often unnecessary) online meetings facilitated working from home (in some cases providing better working conditions), and even more online meetings facilitated nights-in, quizzes or karaoke to connect with friends and family. For some, it was connecting with strangers to make sense of the pandemic or over (new) shared interests. Whatever the reason – for those who had access – the same technologies (hardware and software), were in our homes, blurring work and personal life. For those who had access and those who didn’t, the same disparities and hostilities found in real life were exacerbated. Promises of a return to a pre-pandemic world include measures such as increased surveillance and personal data sharing. Online and tech companies – like many corporations and indeed, nation-states – also have a relentless drive for growth and expansion at any cost. Big companies have always demanded more and more resources, from minerals and human labour required to make the tech, to vital resources such as our personal data and the water usage required to hold it. For example, when American multinational corporation and technology company, Intel Corporation opened its first factory in Albuquerque in the 1980s, a decade later, it was using three million gallons of water a day for production. In 1995, Intel gave public notice that it planned to purchase water rights 70 miles south of Albuquerque, prohibiting current owners from using surface water. This move would allow Intel to drill their own wells, to obtain a cheaper supply of water and moving water usage from agricultural and municipal use to large-scale industrial use. As Elizabeth Martínez writes in De Colores Means All of Us, “the lure, as always, was the promise of jobs, to justify bleeding massive subsidies and natural resources from a poor state”. A recent report by David Mytton in the npj Clean Water journal indicates 29.3 billion devices are expected to be online by 2030, up from 18.4 billion in 2018. To reliably support the online services used by these billions of users, data centres have been built around the world to provide the millions of servers they contain with access to power, cooling and internet connectivity, requiring the use of water. The Information Communications Technology (ICT) sector is responsible for some of the largest purchases of renewable energy but, energy consumption is only one aspect of the environmental footprint of ICT, a less well-understood factor is water consumption. Google and Microsoft (despite the latter changing their methodology) have reported increases in the billions, year on year. Amazon does not publish water figures. A medium-sized data centre uses as much water as three average-sized hospitals or more than two 18-hole golf courses. From the limited statistics available, it is understood that some data centre operators are drawing more than half of their water from sources suitable for humans to drink and cook from (potable water). As the report concludes, “corporate water stewardship is growing in importance, yet it is difficult to understand the current situation due to the lack of reporting. The entire data centre industry suffers from a lack of transparency. However, they will only report data when their customers ask for it”. Technology and nature (humans are part of this) are becoming increasingly entangled, and attention should be focused on how these can work in ways which give back. Not giving back for the sake of doing, or rooted in extractivism, but for our collective good. Returning to “bread and roses”, the collective good must include ways to experience joy and all kinds of sustenance. However, when Assuming the Ecosexual Position, it is important to recognise that this sexy, exuberant joy with(in) nature is not simply a hedonistic hide-out where people can numb themselves and escape from the heavy responsibilities of facing the consequences of climate crisis. On the contrary, it is a state of mind, a way of living and being, that enables people to stay present with grief, loss, fear and accountability rather than living in a state of denial. Or, as Donna Haraway puts it “staying with the trouble”. Within this frame, when the conventional ways of fighting corporate greed and destruction aren’t working – including strike action – it makes complete sense for artists Beth Stephens and AnnieSprinkle (or anyone) to marry a mountain range, or a body of water, in a joyous performance art declaration of love with the community of activists who are in the fight with them (and all of us). As the expansion of media and cultural playgrounds for the powerful are built on the riverbanks of Scottish cities, they dutifully play their part in romanticising the abundance and spaciousness of places where hills and glens are found. Both urban and rural areas in Scotland are then marketed by governments and public bodies as sites for private investment, repeating cycles of erasure of ecosystems and ways of knowing and being. Why not then, re-eroticise the universe and call into question the hierarchy of species? To do anything other, as Katherine McKittrick states in Dear Science and Other Stories, “depicts our presently ecocidal and genocidal world as normal and unalterable’. Our work, she argues, is ‘to notice this logic and breach it”.

By Layla-Roxanne Hill & B.D Owens

Bread, Roses, Coal, Water and the Ecosexual Position was commissioned by NEoN Digital Arts as part of their 2021 programme. Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle’s Assuming the Ecosexual Position exhibition, is showing at Sharing Not Hoarding, Dundee until 16th January 2022.