People Powered Money

Faced with these uncertain post-pre-pending Brexit whatever hell may come days, it might be worth revisiting local alt-currency efforts. When your wallet’s empty it’s all too easy to think that money is the evil torture instrument of an exploitative economy, a sinister tool of somebody else’s capital formation strategy that you have no control over. You might be right, but that’s also not the full story. We all have money making power because anybody can create money. Money is simply an agreed system for representing and exchanging value. It doesn’t even require coins and notes. I could declare cupcakes to be money instead if I wanted to (I quite like that idea, promotes home-baking and quick spending lest the icing on the cake quickly devolves into stale crumbs)… or swap stones for coins (Yah, large stones, were the currency of choice on the Island of Yap in Micronesia, which meant that people had to remember who owned what share because the stones were too big to move…tricky)…or offer points towards air-miles (Sound familiar? Duncan McCann from the New Economics Foundation suspects that air-miles may well be the most valuable alt-currency in the world).

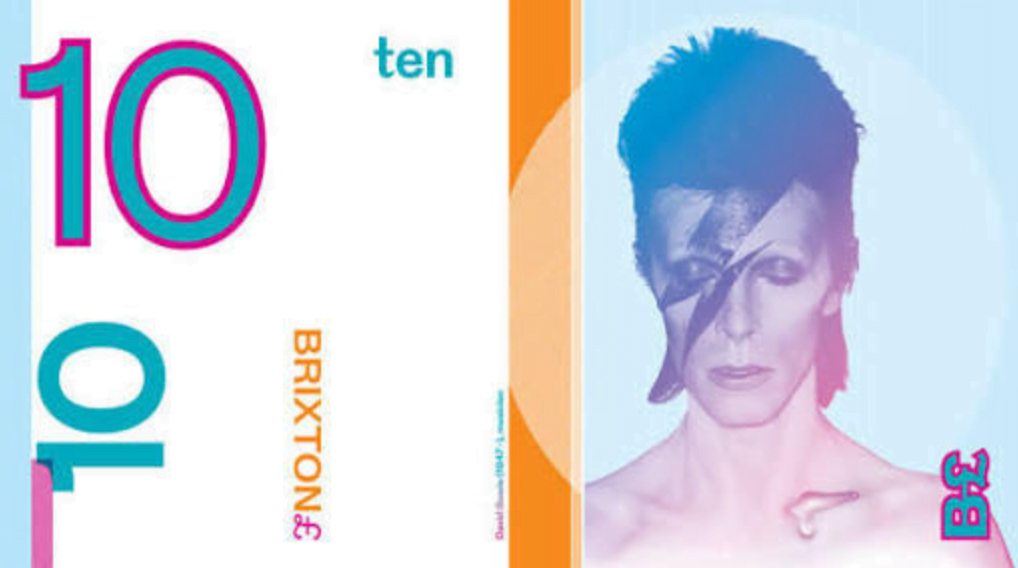

The challenge is not so much making money, as finding people to swap cupcakes with, in other words getting people to accept your icing as their currency. All sorts of communities are already doing just that. Birmingham, Brixton, Bristol and Liverpool all have their own alt-currencies which can be used to purchase discounted local produce, and in some cases pay local tax. The more people use these alt-currencies the more useful they become, to the point that they can even prop up local economies. “The miracle of Wörgl”, for example, is the popular story of an Austrian town that staved off the worst of the 1930s depression by printing its own currency designed to encourage local trade (the currency lost value over time, promoting ready circulation and in turn construction, infrastructure and employment).

Darryl Gaffney du Plooy, one of the co-founders of a social enterprise called Uppertunity, has been working on various Dundee community projects and social services for the past ten years. Lately he has also started to research models of alt-currencies and is now looking to connect with other groups to explore the feasibility of developing an alt-currency for Dundee. I attended an evening seminar that Darryl organised to find out more. Two guest speakers joined us via Skype. One was Duncan McCann, a researcher from the New Economics Foundation in London who has so far helped over six communities both in England and across Europe set up alternative currencies. We were also joined by Alex Walker who is the chair of Findhorn’s community enterprise Ekopia Resource Exchange, a scheme that manages the Eko, their local currency designed to promote local trade and provide low-cost financing for community projects.

Apparently, it’s okay to print your own currency in the UK as long as you don’t adorn the notes with the faces of any known members of the establishment. At least that’s what the Bank of England advised the Findhorn community when Alex Walker started using his own printer and photocopier to issue their first Ekos as a supplement to the local LETS exchange system back in the 1980s. Ekos are issued as a type of community share, which is floated against the pound, so one Eko equals one pound. With about 30,000 Ekos now in circulation, local practitioners trade them amongst themselves and local shops readily accept Eko as it saves them having to pay credit card fees. The added benefit is that people who use the Eko are much more likely to know and chat with their local shopkeepers, because the currency is still unique enough to be a discussion starter. Ekos have also attracted the interest of currency collectors, which helps the community raise funds for affordable housing and similar community interest projects.

Duncan McCann from the New Economics Foundation, advises that in order to turn money into currency, it’s essential to first think through what it will buy and how it can be spent. Each community will want different things. Some communities want to encourage more eco-friendly behaviour. In Belgium, for example, a waste company weighs your rubbish to see how much you should be paid (goodness)! Other communities want to help alleviate poverty, like in Amsterdam where the Makkie time-bank system recognises the value of community volunteers by awarding them one Makkie for every hour spent helping others.

There’s a lot more to alt-currency implementation besides design however. You also need to build the sorts of relationships that will ensure your community goals can actually happen. The Brixton pound, for instance, became a lot more viable when the council came on board to not only offer local currency wage deals, but also accept alt-currency business tax payments, so that local retail outlets started welcoming the Brixton pound with open arms.

The night that I attended the Dundee alt-currency workshop the participants were just starting to think through what sort of local projects they’d like to support. One promising suggestion was to offer banks of food as currency in order to help take the shame out of foodbanks. Others wanted to encourage more happiness, but didn’t know how. Still others wanted to alleviate the impact of precarity in the creative sector – a valuable project!

Alt-currencies can’t make all these things happen like magic, but they are useful tools to help communities do things differently. If you’d like to get involved and help build a new alt-currency future for Dundee, Darryl is reachable on Twitter @DDuPlooy or [email protected].

By Bronwin Patrickson

Image of the Brixton £10 note